【Manga】Is “Ask Him for Housework Gently” Really True?

How much time do you usually spend on household chores?

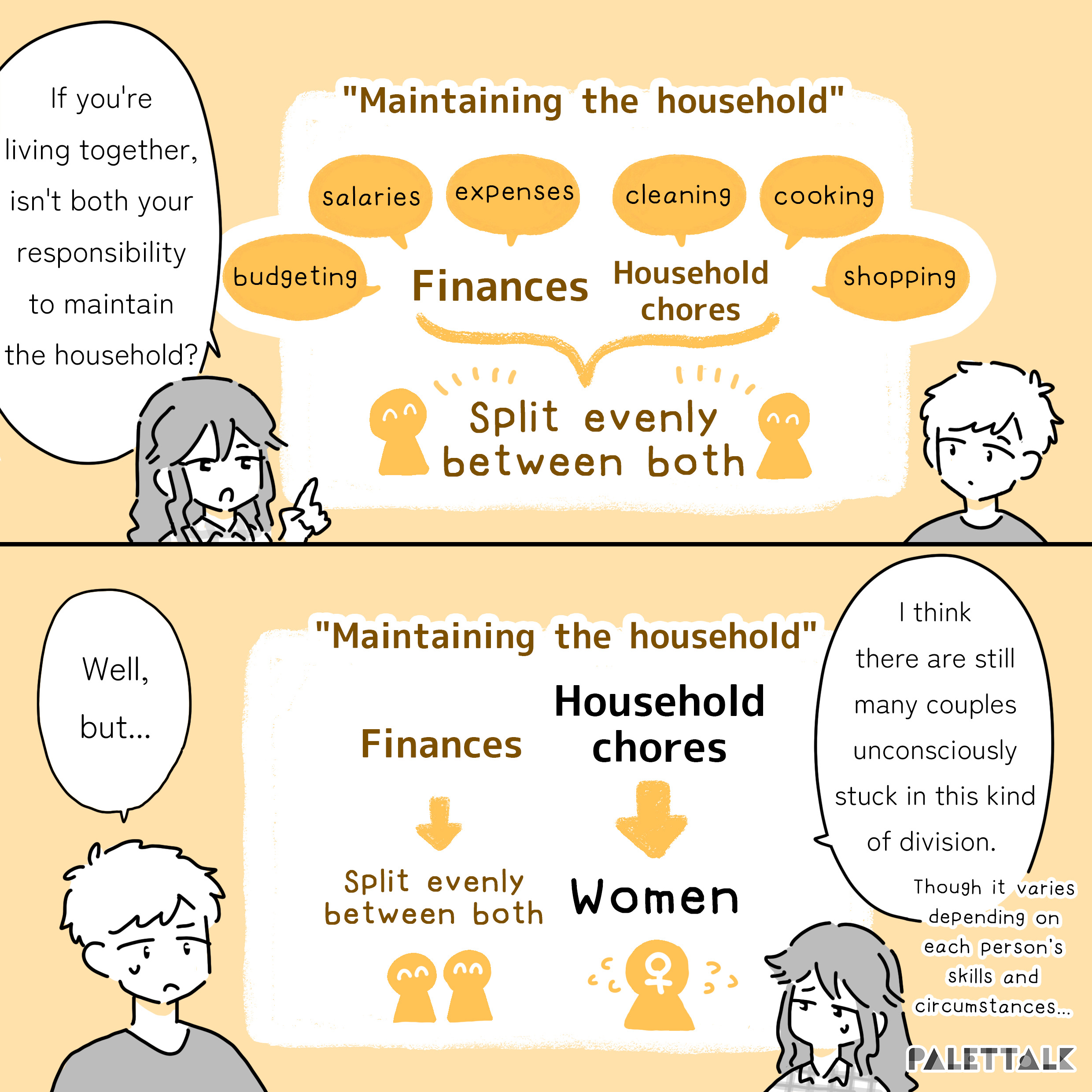

It should vary depending on age, occupation, and family, but in Japanese society, the idea that “women are supposed to do housework” still sticks around. Even among couples where both partners work, it’s often seen that the time spent on housework greatly differs.

In heterosexual couples, among married couples, and at family gatherings, you might notice that “naturally,” women are doing the housework… Many of you might have questioned such situations, haven’t you?

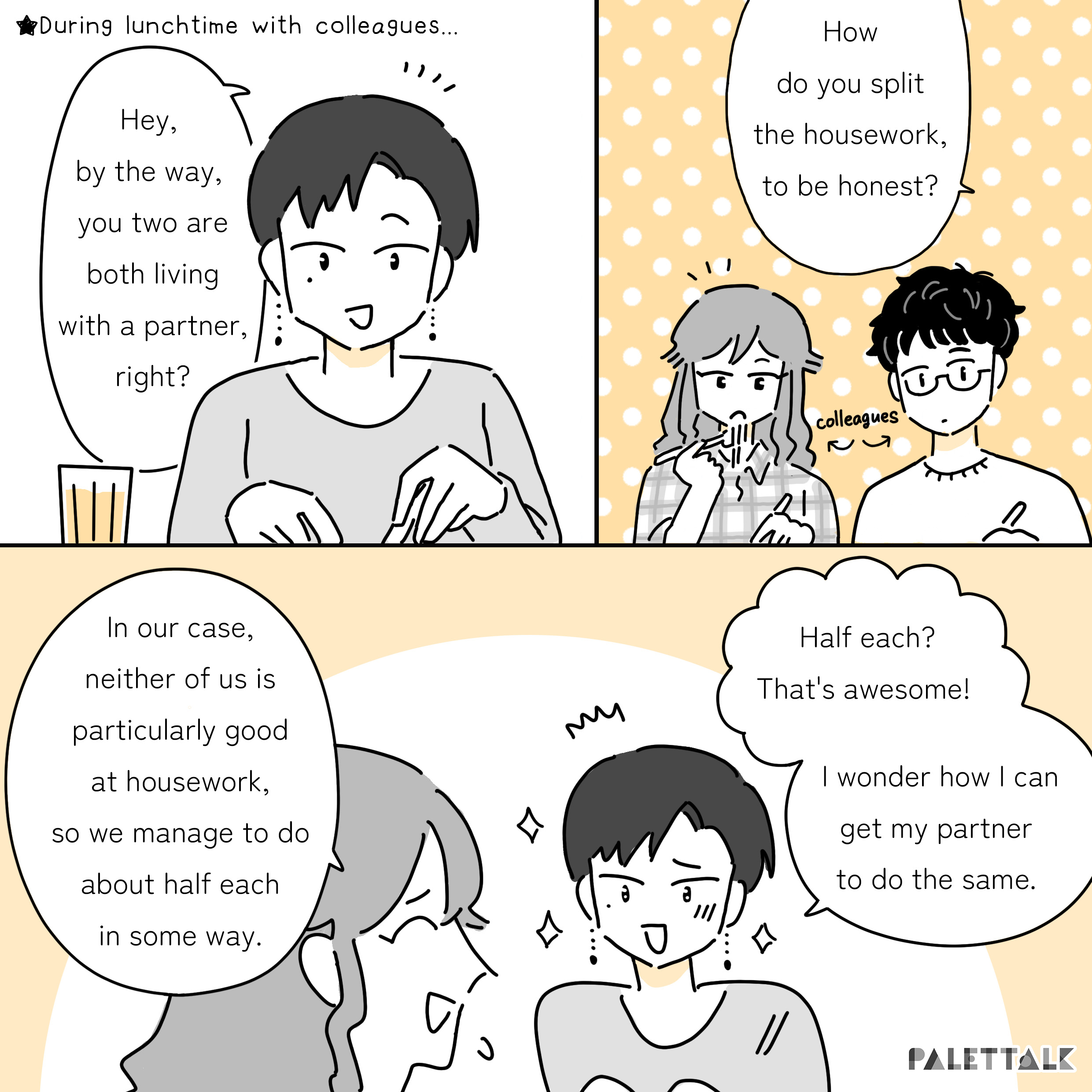

This time, let’s think about these fixed ideas about housework through manga.

There’s No Gender Suited for Housework

When you search for terms like “couples,” “division of household chores,” and “tips,” you’ll often come across articles advising, “Let’s think of ways for wives to encourage their husbands to pitch in more.”

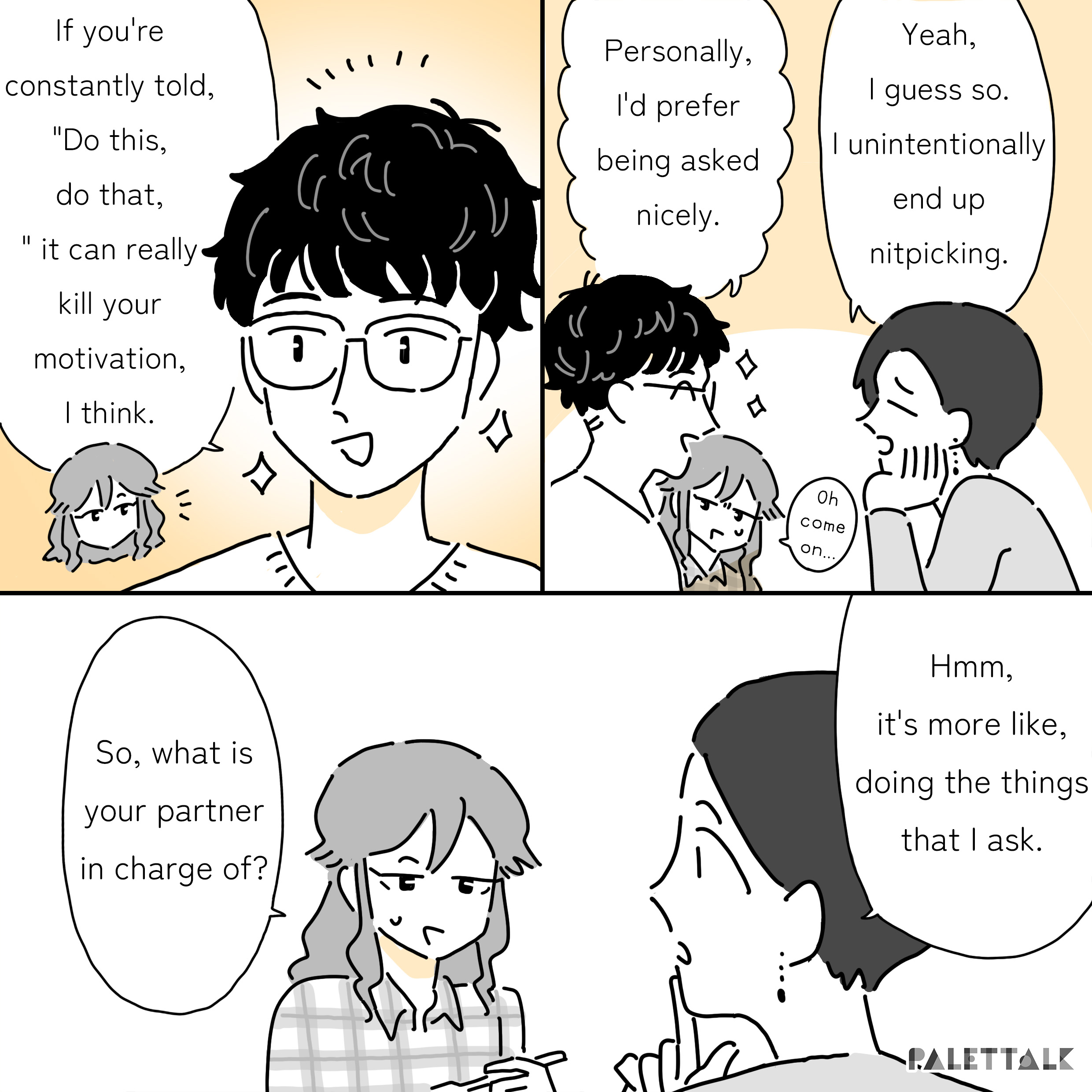

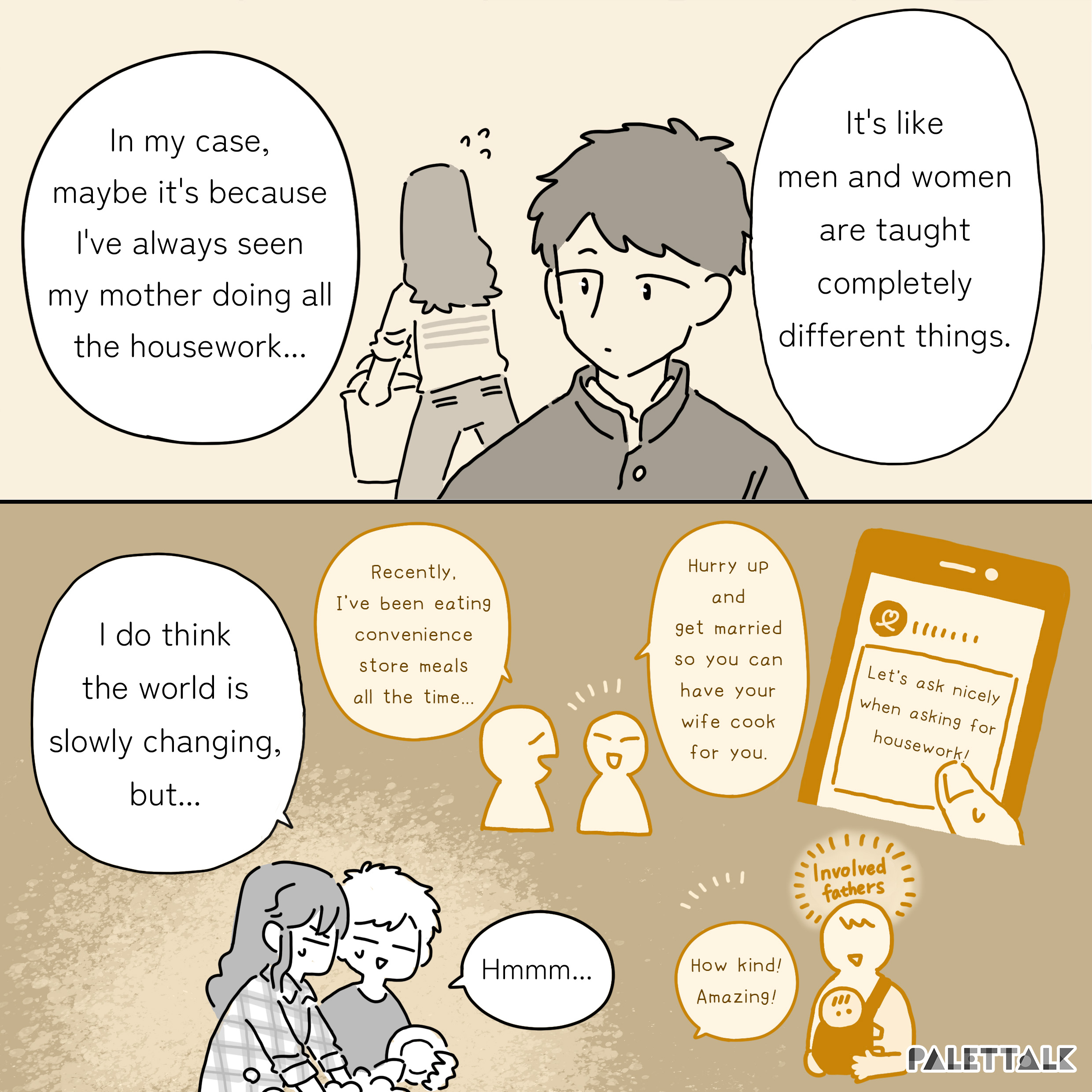

As illustrated in the manga, the mindset that men are just “helpers” rather than equal partners in household chores still remains.

One of the beliefs supporting this mindset is the idea that “women are naturally adept at delicate tasks like housework and childcare, so it’s only natural for them to take on these responsibilities.”

As you may have already noticed, this claim is quite absurd.

There are men who excel at housework, just as there are women who struggle with cooking, cleaning, or interacting with children. This is perfectly normal, as there’s no absolute correlation between gender and proficiency in these areas.

Despite this reality, the stereotype that “women are naturally good at household chores and childcare” has remained. Furthermore, there has been a common attitude that labels women who are not good at meticulous tasks or who struggle with children as “unwomanly” or “immature.” This trend has been overlooked for a long time.

Linking characteristics like “the ability or inability to do something” to someone’s assigned gender at birth using words like “naturally” can cause a sense of discomfort in life for many people.

The advice encouraging women to make arrangements in order for men to pitch in more is disrespectful not only to women but also to men. Also, it’s dismissive of individuals who don’t fit into traditional gender binaries.

Is It Excusable Since Men Are the Ones Making Money?

In addition to the stereotype that “women are naturally good at housework,” another belief supporting this unequal division of household chores is that “men work to support the family, so it’s only natural for women to do the housework.”

When you speak up about household chores being a labor, and each individual should share responsibility, you might hear responses like, “If you’re going to complain, then try paying half of the rent and expenses.”

However, such arguments only hold weight in societies where equal opportunities and wages are guaranteed regardless of gender.

Can we say that today’s Japanese society provides such an environment? Unfortunately, the answer is “NO.”

It’s been almost 40 years since the Equal Employment Opportunity Law was enacted. While the number of dual-income households has increased, there’s still a significant wage gap between men and women.

According to a 2021 survey by the National Tax Agency, the average annual salary for men is ¥5.45 million, while for women, it’s ¥3.02 million, and the gap is obvious.

Moreover, while the majority of men earn between ¥4 to ¥5 million annually (17.5%), the majority of women earn between ¥1 to ¥2 million (22.5%).

Considering such wage disparities, it’s clear that when one partner in a heterosexual couple needs to take leave or quit work for childcare, it’s “naturally” the woman, who typically earns less, who ends up leaving her job.

(When we say “naturally,” it’s not because it’s natural but because various factors such as wage gaps and societal beliefs suggesting that mothers should take care of children create situations where there seems to be no other choice.)

Furthermore, in a capitalist society where livelihoods depend only on money, those without income unavoidably have to obey those with income.

Therefore, women with relatively low incomes or those who have no income due to childbirth or child care often find themselves in weaker positions compared to their male partners who “earn” more.

When a stay-at-home wife considers that she might not receive financial support if she opposes her husband, or that she might not be able to support herself after divorce, there is clearly an imbalance of power.

In such structures where individuals have little power, demanding sacrifices by holding money hostage with statements like “I’m the one earning, so you should endure it” amounts to emotional abuse.

In such structural circumstances where individuals have limited options, making statements like “I earn the money, so you should just suck it up” and using money as a “hostage” constitutes emotional abuse.

The people who should deal with the difficulties caused by expectations like “men should support the family” are companies and society. Making partners go through similar hardships doesn’t solve anything.

Ignoring existing imbalances within relationships and saying “if we share housework, we should split expenses equally,” doesn’t work in reality.

Household Chores Aren’t Just “In-House Issues”

The wage gap mentioned earlier is closely tied to the structure of the labor market, which operates with male standards.

Stereotypes like “women can’t handle tough tasks” or “they’ll eventually take maternity leave” often block women’s hiring and promotion opportunities. Under the belief that “men should be the breadwinners of the family,” men are more likely to occupy higher-paying positions.

It’s unacceptable to load men with tough tasks simply because they’re men, and assuming that only women need to take parental leave is biased. Running organizations in a discriminatory manner towards women suggests that there might be a lot of gender harassment against men too.

Ideally, there should be a system where taking parental leave is easy for everyone, regardless of gender. Besides, just because someone is a woman doesn’t mean they’ll definitely have children.

Household chores, often seen as solely domestic concerns, are actually closely linked to the structure of society.

Unfortunately, even if women find jobs, the tendency for women to take on most of the household chores doesn’t seem to improve.

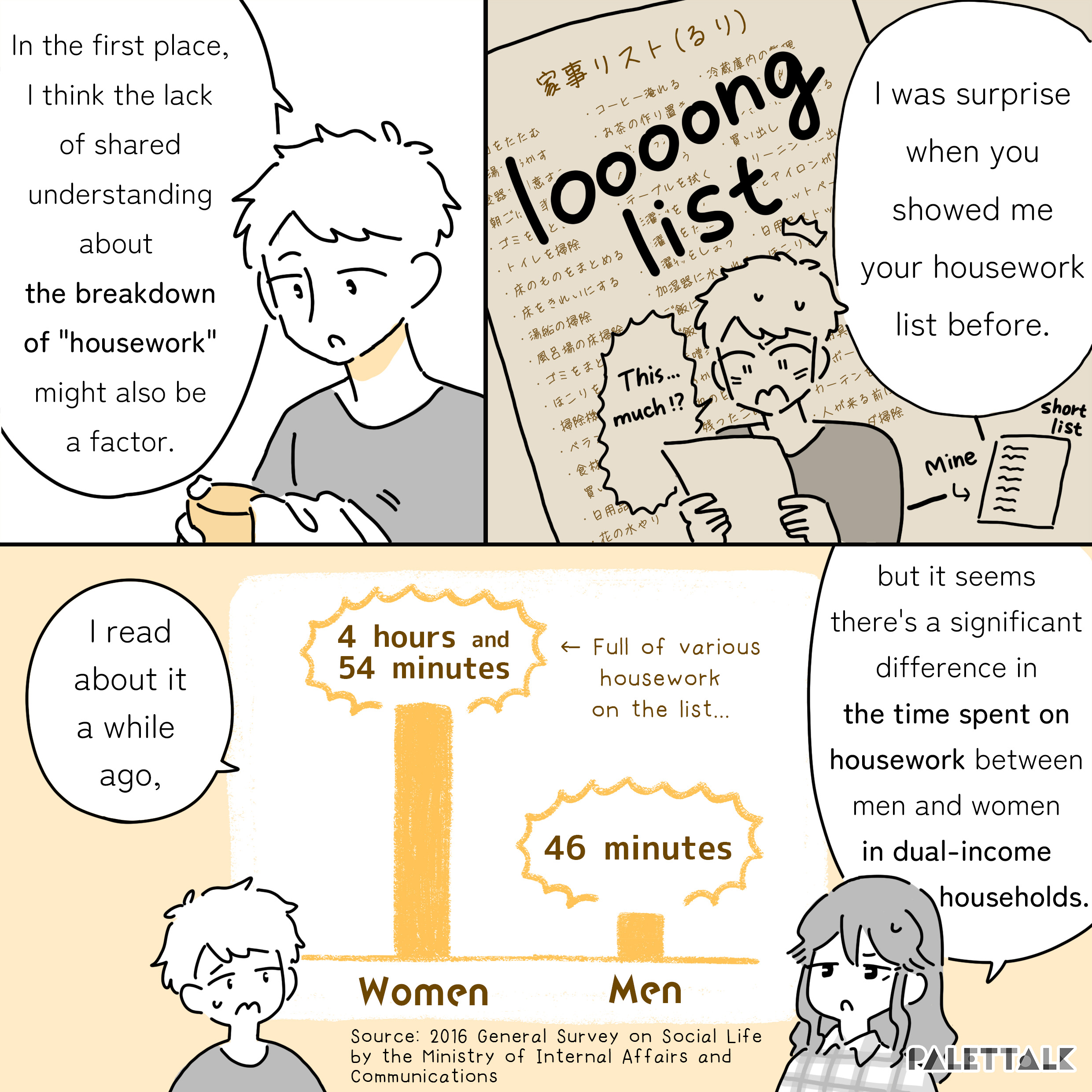

As mentioned in the manga, according to the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, in households where both partners work, wives spend an average of 4 hours and 54 minutes on household chores per week, while husbands spend only 46 minutes.

The increase in working women might give the impression that they’re now on equal footing with men outside the home.

In reality, women are simply adding more tasks to their plate, like managing household chores along with going out to work for the family.

The norm that expects women to be both “dedicated wives” and provide “labor force” reinforces the pressure that “husbands should be the ones supporting the family.”

To break free from this cycle, it’s essential to gradually reassess gender stereotypes and the societal and organizational structures built upon them.

Conclusion

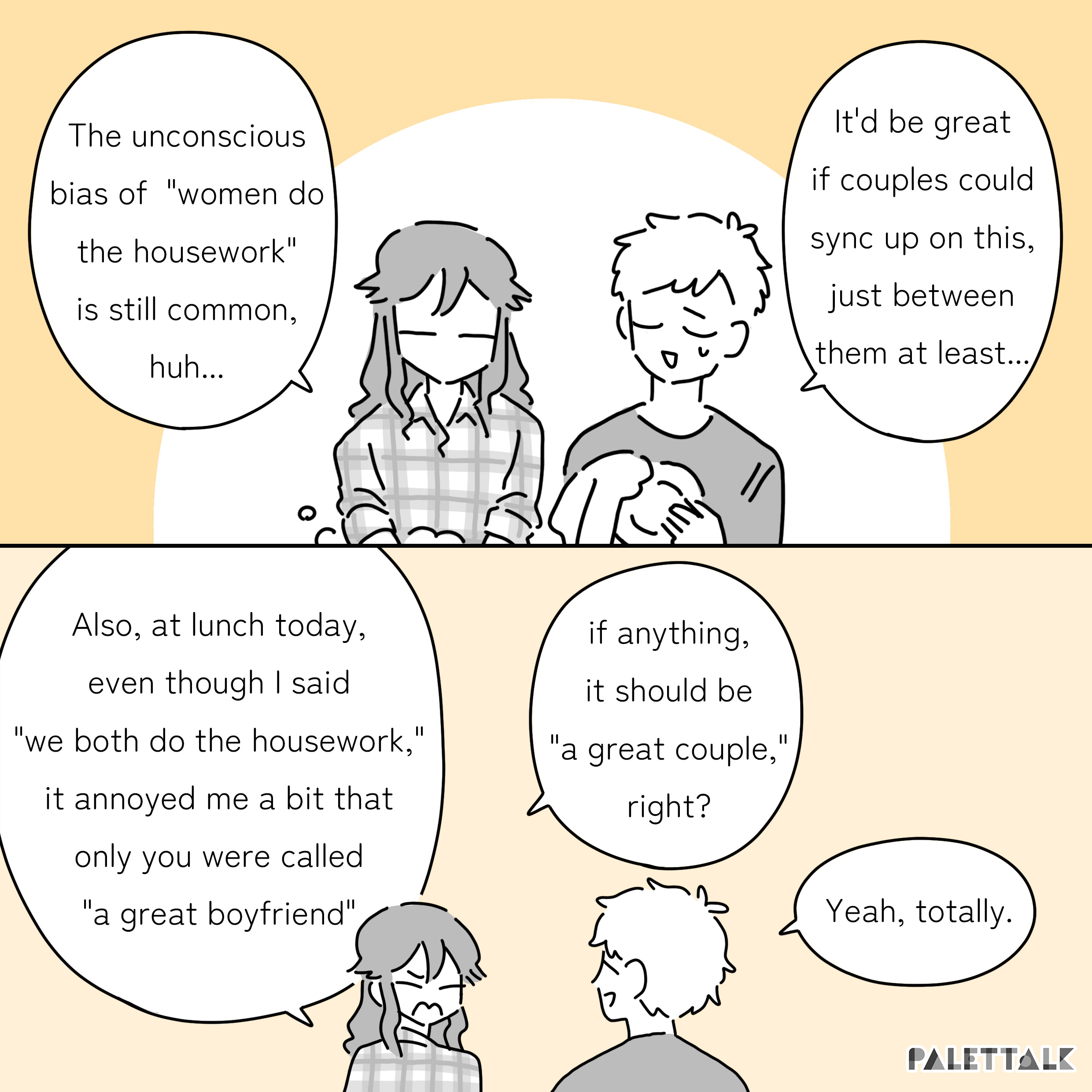

In this article, we explored the dynamics of household chores, gender, and work through a manga depicting the division of household chores among heterosexual couples.

When we place value on labor “outside the home” where money is exchanged, we tend to overlook the challenges of labor “inside the home.”

Additionally, household chores, which are performed to maintain the comfort of living spaces, often go unnoticed unless they are not done properly.

For instance, it’s only when we realize the clothes we intended to wear haven’t been washed or when the forgotten trash bag starts piling up in a corner of the house that we finally notice the undone (or neglected) chores.

Therefore, as seen in the manga with the main couple, creating a household chore list can be helpful to visualize and organize the chores necessary for shared living.

It would be great if we could visualize the household chores necessary for the shared living and divide them based on individual strengths and weaknesses, rather than reasons like “because you’re a woman” or “because you’re a man,” to support our life together.

(Translation: Jennifer Martin)